The Ultimate Guide To Probiotics

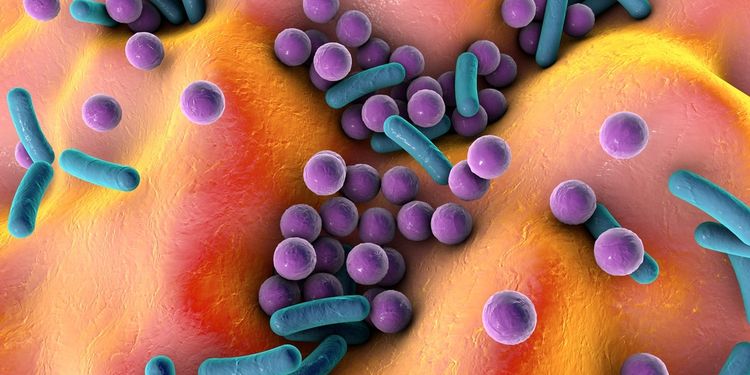

You may be shocked to find out that we humans may just be a fancy ride for the trillions of microorganisms that inhabit our bodies. The nose, ears, and entire digestive tract from mouth to anus are all lined with mostly bacteria, but also with different types of yeast, fungi, and protozoa that live in harmony with one another (most of the time).

So why isn’t everyone walking around sick? Aren’t bacteria the culprits in illnesses such as tuberculosis, salmonella (food poisoning), and Lyme disease? It turns out that not all bacteria are created equal. The microorganisms that inhabit our bodies are collectively referred to as the microbiome, which has recently attracted a lot of attention in health research. In fact, we’re finding out that the proper function of the microbiome, as determined by the types of microorganisms and their ratios to one another, is vital to maintaining good health.

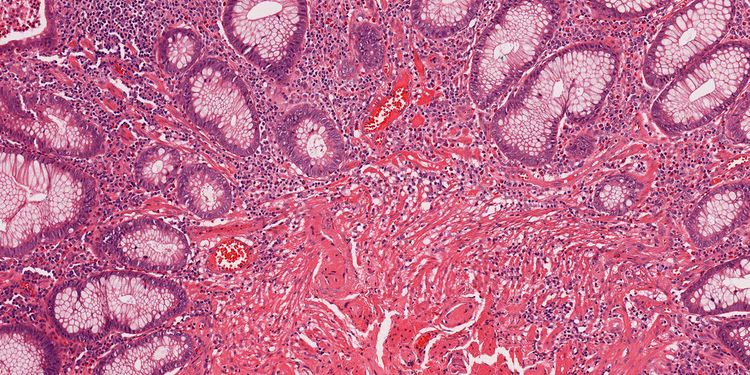

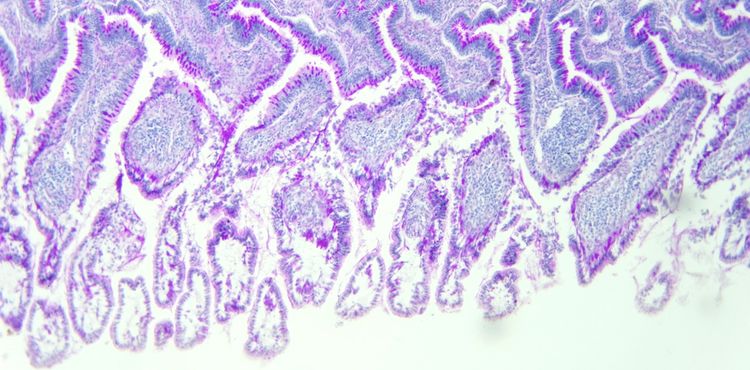

Although we tend to think of our skin as the largest barrier between the outside world and the inside of our bodies, this role actually goes to our digestive tract. You can think of this tract as a long tube whose inside lining only allows certain beneficial materials to enter the body when it’s functioning normally.

In essence, what enters our mouth and exits our anus was never technically inside our body at all. According to Chris Kresser, a functional medicine practitioner and expert in ancestral health, the surface area of our digestive tract is 100 times that of the skin, making it the largest interface between our body and the outside world. The success of this interface in its ability to absorb essential nutrients while keeping out foreign invaders is in large part due to the microbiome.

Getting To Know Your Bacterial Co-Habitants

Humans have evolved with, and potentially because of, our mutualistic relationship with bacteria. They’re actually often responsible for protecting against infection, not causing it. This protection is multifaceted.

The good or “non-pathogenic” bacteria colonize your intestines, leaving little room or resources for the “pathogenic” or bad bacteria, yeast, fungi, and parasites. These good bugs also produce anti-microbial materials that create a hostile environment for the bad bugs.

Kresser reports that 70-80% of the immune system resides in the gut’s associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). This tissue is modulated by the bacteria that reside with it, prompting the release of either inflammatory or anti-inflammatory chemicals. It’s thought that the immune system does a routine sampling of the microbes present, keeping our main defense mechanism primed and ready to spring into action against more formidable guests.1

Bacteria may be able to regulate the opening and closing of the tight junctions in your epithelial cells, or the cells lining the intestines.2,3 This has huge implications in the development of leaky gut, a predisposing disorder to autoimmunity, in which the tight junctions are compromised, leading to chronic inflammation.

Your good bacteria are also important for you in order to process raw materials that you’re not able to break down. Sayer Ji, founder of greenmedinfo.com, comments on the ability of microbes to both produce useful nutrients, such as B vitamins, and break down dangerous compounds, such as pesticides. They also eat the foods that you aren’t able to digest on your own, like certain types of starch and fiber, converting them to absorbable short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) that have anti-inflammatory, cancer-preventing, and cholesterol-lowering properties.4-6

Lots Of Buzz About Probiotics

The word “probiotics” literally translates to “for (pro) life (biotic)” for their ability to positively impact the function of the living bacteria in our guts. Probiotic foods or supplements are composed of microorganisms that are similar to the good bacteria found in a healthy gut. These tiny organisms can influence the environment in our gut to make it favorable for our good bacteria to flourish. In doing so, these good bacteria protect and maintain the function of our gut barrier and immune system, the body’s first line of defense from foreign invaders.

Due to their beneficial effects in the gut, probiotics have been used in the treatment of digestive disorders such as diarrhea, constipation, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, and even Celiac disease, an autoimmune condition triggered by gluten that causes digestive distress.

However, a healthy microbiome may also be critical to preventing many other chronic diseases of the modern age, such as autoimmunity, heart disease, and certain types of cancer. Thus, even in the absence of blatant digestive troubles, it might be a good idea to promote the abundance and diversity of the good bugs in your gut.

Why You Might Need Probiotics

“If I already have bacteria in me, why do I need to take more in the form of probiotics?” you may ask. Unfortunately, there are many factors working against the bacteria we already have. Although necessary to wipe out nasty, deadly bacterial infections, antibiotics (meaning “against life”) aren’t always reserved for severe infections. It’s common for primary care physicians to prescribe antibiotics for the common cold, ear infections, sinus congestion, or even in preventative situations like before a trip to the dentist or to avoid traveler’s diarrhea. Almost everyone has been prescribed antibiotics at least once in their lives.

What we’ve failed to recognize until recently is that, unfortunately, out with the bad means out with the good as well. Repeated antibiotic use can lead to dysbiosis, or the overgrowth of bad bacteria and fungi, and a decrease in the diversity of gut bacteria. According to Dave Asprey, founder of The Bulletproof Exec, just one round of antibiotics can permanently alter your gut microbiome.7

To add insult to injury, we’re a very germophobic society in general and don’t regularly come into contact with bacteria, good or bad, to keep our immune systems active. Scrubbing even our organic veggies, traveling with antibacterial solution in our pockets, and hydrating with chlorinated water are just a few of our antibacterial behaviors that may cause more harm than good.

Other factors that have been shown to affect your gut bacteria include stress, medications, toxins such as heavy metals and pesticides, and a diet high in refined flours, sugars, and oils. Since these factors are omnipresent in the modern world, there may be many things affecting the health of your good bacteria. Consequently, many of us are walking around in a state of dysbiosis, even if we don’t manifest digestive symptoms.

How Probiotics Work

The mechanism of action that probiotics take is much more complicated than a simple additive effect. As a result, it’s incorrect to assume that a wiping out of the beneficial flora with a round of antibiotics can be reversed by simply adding more bacteria. These good bugs are important for immune stimulation, competitive inhibition of the binding of pathogens, and stimulating the regulation of the tight junctions, or gateways, between our intestinal cells. There are a couple of ways probiotics have been shown to influence the above factors:

Probiotics can upregulate the genes in the intestinal lining to produce mucigen, or the precursor to mucus, which has a protective effect on the lining of the gut.2,9 Mark Sisson, an expert in primal nutrition, points out that some bacteria actually eat the mucus, prompting the production of more mucus.

The bacteria in probiotics can produce antimicrobial compounds such as lactic acid, bacteriocins, and hydrogen peroxide, as well as increase your own production of antimicrobial peptides, or proteins.2,10 These compounds make the gut an unfavorable environment for the bad bugs.

Probiotics have also been shown to positively influence the regulation of tight junctions and increase the absorption of beneficial nutrients while minimizing absorption of undigested or infectious material. One possible mechanism for this is the activation of particular receptors that upregulate chemicals related to repairing the epithelial cells—the cells that line the gut.2

Contrary to popular belief, probiotics don’t necessarily set up camp permanently to influence our gut health. Most research shows that the colonization or proliferation of bacterial cells attached to the gut lining may only be temporary. This supports the idea that the beneficial effects of probiotics may be attributed to the change in the gut environment, allowing our inherent good bacteria to regain their strength.

Read Those Probiotic Labels

There are many different species, or specific types of bacteria used in probiotic foods and supplements. Most supplements have at least two, and some have over ten different species. The naming of the bacteria used in the supplement should be listed according to genus, species, and sometimes the specific strain.

For example, a probiotic label that reads, “Lactobacillus acidophilus L5” incorporates a bacteria belonging to the Lactobacillus genus, the acidophilus species, and is of the L5 strain. Some probiotics abbreviate the genus name to just the first letter, such as L in this case, so it reads L. acidophilus. Not all probiotics are required to list the particular strain of bacteria since bacteria of the same species are very similar to one another. However, this might be an indicator of supplement quality, since providers must pay extra to have a named strain.

Usually, the amounts of bacteria in a probiotic are listed in terms of their colony forming units (CFUs). This number represents the number of live organisms at the date of manufacture for most probiotics. Some probiotics are listed in terms of grams when their colony forming potential can’t be measured at the time of manufacture. This doesn’t necessarily mean that these probiotics are less potent, but you can’t be positive about how much active bacteria you’re actually getting.

The Different Classes Of Probiotics

Labels often vary between the different classes of probiotics. There are many different vehicles for probiotic supplementation, but the main ones include:

Fermented foods: This is the whole food form of probiotics and includes unpasteurized and raw sauerkraut or pickled vegetables, kimchi, beet kvass, kombucha, yogurt, kefir, and other products that use and contain live bacteria and/or yeast. In the process of fermentation, the microorganisms feed on the naturally-occurring sugars and convert vitamins and minerals to their more absorbable forms; this is similar to what happens when these organisms get inside your gut.

Probiotic supplements: If ferments just aren’t your thing, or you’d like to know exactly what bacteria you’re getting, you can supplement with probiotics in their isolated forms. Probiotic supplements can be broken down again into three main categories:

- Lactobacillus and/or Bifidobacterium-based: These supplements are made with bacterial strains that are known to inhabit the gut. Chris Kresser points out that in the modern western gut, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains together account for roughly 30 trillion of the 100 trillion microbes in the gut. Supplements in this class may also contain species like Streptococcus thermophilus, a strain that’s used for most dairy ferments and is also known to be present in the gut in smaller quantities.

- Soil-based organisms (SBOs): SBO supplements contain bacterial strains that are commonly found in the soil, like the Bacillus genus, rather than in our gut. It’s thought that our exposure to healthy soil, which is significantly low in the modern world, is critical for stimulating the immune system. Although some species may be found in our gut, these organisms are much more prevalent in the soil.

- Yeasts: Some yeasts are used independently or in concert with bacteria as probiotics. Saccharomyces boulardii is the most well-known for its ability to reduce pathogenic yeast and mitigate symptoms of inflammatory and infectious diarrhea.11,12

Some probiotic supplements will incorporate a combination of the above classes of bacteria. There are benefits and drawbacks to each class, which we’ll get to momentarily.

Probiotic Bacteria Should be Alive When They Get To Your Intestines

When considering a probiotic food or supplement, it’s important to consider the stability of the live organisms. This stability differs between types and forms of bacteria. Things like light exposure, heat, moisture, and susceptibility to stomach acid can all affect the potency of your probiotic. It’s important to take these factors into consideration when you’re picking a probiotic.

Liz Lipski, a certified nutritionist and an expert author in digestive health, recommends Lactobacillus/Bifidobacterium and S. boulardii supplements, but only refrigerated forms, since they’re heat-sensitive. It’s also a good idea to get the ones in light-blocking containers, since they’re also susceptible to light.

Pay attention to manufacture dates, as the CFUs are usually determined on this date. Since most of these products are freeze dried in a state of suspended animation, you should limit their exposure to moisture, including the moisture in the air, so that they aren’t reactivated before use. Encapsulated forms in either microspheres or beadlets may also improve their ability to survive your stomach acid.1,13

Experts like Mark Sisson and Chris Kresser advocate the use of SBOs and comment on their natural ability to withstand many of the previously mentioned variables. Most of these organisms are sporogenic, meaning they’re encased in tiny seed-like enclosures that protect them from heat and acid digestion, ensuring safe passage to the intestines. Thus, SBOs have a longer shelf life and don’t require refrigeration, making them more durable during production and travel.

Increasing Good Bacteria Might Be Uncomfortable At First

Before you begin your probiotic regimen, it’s important to consider what you already have going on in your gut. Any underlying imbalance in microbes may have been existing in your gut for a long time. Consequently, overgrown bad bugs may not leave quietly. Adding probiotics to the mix may result in a war for territory within the gut, leading to some undesirable symptoms at first.

Liz Lipski describes in her book, Digestive Wellness, that it’s common to have diarrhea, gas, and/or bloating as the new bugs settle in the gut. Although she recommends high dosages (between 25 and 100 billion CFUs depending on the level of bacterial depletion), Lipski emphasizes the fact that as the bad bugs and yeast die, they release toxins that may worsen symptoms.

It may be smart to titrate your probiotic dose, starting very low and gradually building up to higher dosages. If that doesn’t work, sometimes working with a single strain at first may be tolerated better. Lipski also comments that having adverse effects may actually indicate that the probiotics are doing their job. However, if undesirable effects are persistent or become more severe, you may want to consider stopping your probiotic and investigating other gut disorders that may be aggravated by probiotic use.

There are Some Instances When Probiotics Make Things Worse

There are specific instances when the adverse effects of probiotics may not be indicative of good things going on in the gut. Since there’s a wide range of mechanisms of action between species of bacteria, certain species may aggravate pre-existing conditions rather than improve them.

Histamine Intolerance: Histamine is an inflammatory chemical that’s involved in allergic reactions. If you have a histamine intolerance, your body can’t break down histamine as fast as it accumulates in the gut from normal bacterial metabolism and histamine-containing foods. With this intolerance, you have to be careful about the types of bacteria you consume initially. Some strains of bacteria increase the production of histamine.

Most microbially-produced foods, such as cheese, wine, beer, alcohol, processed meats, and even some healthy fermented foods contain high levels of histamine. Dave Asprey details the mechanisms of histamine intolerance on his blog in great detail, since he himself suffers from histamine intolerance. He writes that strains of Lactobacillus casei, reuteri, and bulgaricus actually increase histamine, while Bifido infantis, longum, Lactobacillus plantarum, and some SBOs can degrade histamine.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO): This is a disorder resulting from too much bacteria and in the wrong place (the small intestine rather than the large intestine or colon). According to Chris Kresser, these bacteria produce abnormally high levels of a particular type of lactic acid, called D-lactate, that causes a wide range of symptoms, from bloating and brain fog to anxiety. Chris Kresser points out that Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium supplements produce the substance in high amounts, while SBOs do not. Thus, Kresser recommends SBOs in cases of SIBO.

In both of these conditions, it may be necessary to first starve the bad bacteria by cutting off their food supply, even from healthy food sources.

Your Probiotics Eat What You Eat

Think of your current state of dysbiosis as the wilderness, your overgrown bacteria or yeast as a pack of wolves, and your probiotic bacteria as a litter of puppies. The wolves have been able to set up camp because the environment is favorable for them.

Introduce a litter of puppies, and although they might stir up some activity, they probably won’t do so well themselves if you don’t alter their environment to make it favorable for their success. Fortunately, there are things you can do to make sure the little guys are able to grow strong and contend with the wolves.

Dr. Sara Gottfried, a Harvard Medical School MD, recommends the following list of dietary changes to alter the environment in your gut, making it habitable for your good bacteria.

- Add resistant starch: Resistant starch is starch that we can’t digest, making it a good food source for our bacteria. This type of starch is usually heat-sensitive and is found in cooked and cooled potatoes, raw green bananas, raw plantains, and potato starch.

- Add prebiotics and probiotic rich food: Fermented foods naturally include both prebiotics and probiotics, making them a good addition to your diet if you can tolerate them. Jerusalem artichoke is also well-known for its high prebiotic content.

- Increase cruciferous vegetables: These include broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and kale, all of which contain prebiotics as well as important anti-cancer compounds.

- Remove sugar: Dr. Gottfried recommends removing refined sugar, in all forms, and being diligent in checking labels on dressings, sauces, and drinks, as these often have hidden sugars. Sugar promotes the overgrowth of pathogenic species of bacteria, predisposing your gut to dysbiosis.

- Increase dietary fiber: Both soluble and insoluble fiber can be good prebiotic foods and can be found in high amounts in fruits and vegetables. The good bacteria preferentially feed on fiber, defending against dysbiosis.

The Latest Probiotic Research

Dr. Kelly Brogan, an integrative and holistic psychologist, writes, “We barely know what we’re doing when it comes to probiotic supplementation.” Although this seems to discredit the use of probiotics, Dr. Brogan also points out that maintaining the health of our microbiome may be an extremely important area of focus in combatting modern disease.

Although probiotic research is still in its infancy, there’s a growing body of research to substantiate its health claims. Sayer Ji reports that probiotics are shown to be clinically effective at treating close to 200 diseases and symptoms, based on the existing research.

It’s important to note that in response to the demand for probiotics, there may be some questionable products comprising the growing multi-billion-dollar industry.14 This makes it extremely important to research your probiotic of choice, considering clinical research that supports your product and whether or not it’s coming from a reputable source.

Ultimately, the successful incorporation of probiotic supplements or foods is entirely dependent on diet and lifestyle changes. If you’re living in a state of dysbiosis, there’s probably a reason for how you got there, whether it be a couple rounds of antibiotics or other medications, too much sugar and flour, excessive alcohol intake, high levels of stress, exposure to environmental toxins, not enough exposure to environmental bacteria, or all of the above. All of these factors will derail any progress made in maintaining a healthy microbiome, regardless of probiotic intake, and should always be considered when addressing the health needs of the gut.