How Inflammation Is Burning Your Health

Chronic inflammation = disease. This is a profound statement that has broad ramifications for health and disease management everywhere.

If you look at the root causes of almost every single disease and death, you’ll notice that chronic inflammation is a player in the process.

Some inflammation is good—in fact, it’s a normal, healthy biological process. It’s only when inflammation goes unchecked for extended periods of time that it becomes a big problem.

Think of inflammation as a smoldering ember. If you have a few embers in one room of a 10-story building, it’s a small problem that’s contained. But if you have embers in every room on every floor of that 10-story building, now there’s a problem. Just a little puff of air might rekindle these embers into an actual fire again. Eventually, the heat from this small fire could grow, and the whole building could go up in flames.

This is similar to what happens in the body. A minor infection might cause a fire that turns into smoldering embers, and these embers die out when the infection is gone (if you have a healthy immune response).

If you’re stressed out, not exercising or sleeping well, or have poor nutrition, imbalanced hormones, and GI problems, there’s a good chance you have smoldering embers burning throughout your body, creating a low-level systemic fire.

If you don’t identify the causes of these small fires, they’ll wreak havoc on your body and cause full-blown diseases like diabetes, heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, dementia, stroke, autoimmune conditions, or hundreds of other major diseases.

The good news is that the power to change this is in your hands, because every action you take each day either contributes to health or causes disease.

What Exactly is Inflammation?

Inflammation is a big buzzword in the world of health now, and rightfully so. The word inflammation comes from the latin word “inflammare,” meaning “to ignite,” and it’s your body’s response to danger signals.

Classically, inflammation describes the body’s immune response and biochemical processes to remove harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, toxins, irritants, or even damaged cells in an attempt to preserve itself and heal. Then we have the physical manifestations of inflammation: calor (heat), rubor (redness), dolor (pain), tumor (swelling), and loss of function.

This process is apparent when you have a cut on your arm, a bad sunburn, or a pimple. It’s less obvious when you have a viral or bacterial infection, since you can’t see the signs. What we’ve described here is acute inflammation. Acute inflammation is a normal process necessary for life; it allows you to survive scrapes and infections. It has a beginning and an end.

Conversely, chronic inflammation persists without end in response to hidden infections, toxins, chemicals, and/or foods or from lack of counter-regulatory mechanisms (chemical “off” switches) in the immune system that should turn inflammation off.2 Persistent cellular stress or dysfunction caused by a high calorie, low nutrient diet, oxidative stress, and hormone imbalances perpetuates this process.

Chronic inflammation is never a good thing. The major danger with chronic inflammation is that it’s silent, causing destruction for years or decades before it’s noticed (usually as the first signs of a disease), leaving significant damage in its wake.1 It could be raging inside you at this very moment without you even noticing. This kind of inflammation is what underlies almost every chronic illness and disease known to man.

Acute and chronic inflammation share a common origin, although they end with two very different products. The main differences between the two processes are:5

Acute Inflammation:

- Elimination or isolation of the stressor (infection, toxin, chemical, etc.)

- Usually a local response (anaphylaxis is the exception)

- Usually adaptive with an appropriate response that begins and ends

- Usually short in duration

Often noticeable

Chronic Inflammation:

- Maladaptive (the normal mechanisms that quench inflammation aren’t working)

- Self-perpetuating/self-limiting

- Disrupts normal balance (homeostasis) in the body

- Alters normal cellular function

- Destroys cells and tissue over time (like the degeneration of joints in arthritis)

- Long duration (months to years)

- Often unnoticeable or hidden

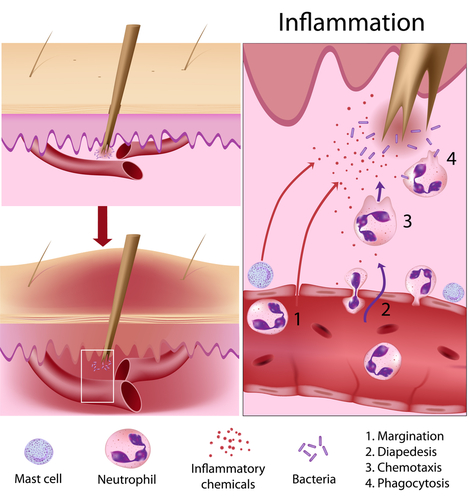

How Does Inflammation Occur?

The inflammatory process is a complex symphony of the response of the immune system and its interaction with many different types of cells and biochemical signals.

There are two main branches—the innate immune response, which occurs quickly and is more simple and nonspecific, and the acquired immune response, which occurs more slowly, as it’s more specific and has memory (so when you encounter the same trigger, such as a virus, your body is prepared for the attack).

Triggers, such as infection or injury, induce a series of biochemical events. Numerous substances are released simultaneously by the injured tissues, causing changes to the surrounding tissues.6

Remember our 10-story burning building? You can think of your injured tissue doing this just like you would turn on the sprinklers to dampen the fire and alert the fire department.

There are many chemical messengers that function in this process; however, the important ones to note are histamine, serotonin, bradykinin, lipid (fatty acid) derived mediators, cytokines, and acute phase reactants.

These chemicals are the “fire department,” with their many tools to put out the fire. They’re responsible for actions such as swelling (increased leakiness of the blood vessels), relaxation (dilation) or tightening (constriction) of the blood vessels, airways, and intestinal smooth muscle, and sending out chemical messages that turn on genes, recruit more helpers to the scene, or produce substances involved in the inflammatory process itself.

Histamine: Most people are aware that histamine is involved in the inflammatory response given the significant notoriety of antihistamines with allergies.

What many people are unaware of is that it also functions as an excitatory (stimulating) brain neurotransmitter producing wakefulness and anxiety, which is why many people with severe allergies, hives, or GI infections don’t sleep well.5,6 Its highest concentrations are in the gut, skin, lungs, and central nervous system (CNS), where many of the symptoms are felt.

Serotonin: This substance is best known as a brain neurotransmitter responsible for keeping you happy, calm, and well-rested. It’s also known for its role in the gut, affecting motility (how food and waste move through) and secretion of digestive chemicals. 95% is produced in the gut, and it can be significant in inflammatory GI disorders. You know that feeling when you get butterflies in your stomach, then have anxiety and maybe diarrhea? That’s serotonin. Together, histamine and serotonin are some of the first responders in the inflammatory movement.3,5

Bradykinin: This protein isn’t well-known by name; however, you’ve felt its effects many times before, since it’s a significant chemical in the inflammatory process. Bradykinin causes many of the actions of the inflammatory process (swelling, pain, blood vessel dilation, etc.) itself, or it signals other cells to participate and release their chemicals. It can also increase histamine release, making a response more intense.4 Bradykinin is most often released from tissue damage or exercise.4

Lipid Derived Inflammatory Mediators: This is a fancy term for chemicals derived from the oxidation (the loss of electrons from molecules—think rust) of the omega-6 fatty acid, arachidonic acid (AA), and omega-3 fatty acids’ eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

Like histamine, you may have heard of some members of this group of chemicals before, since prostaglandins and leukotrienes are called out in the inflammatory process in advertisements.

They’re short-lived, signaling molecules found in most cells that modulate all aspects of the inflammatory process, including the resolution of inflammation, and they have system-wide influence on nerve transmission, mood, and hormone secretion.5,7,8

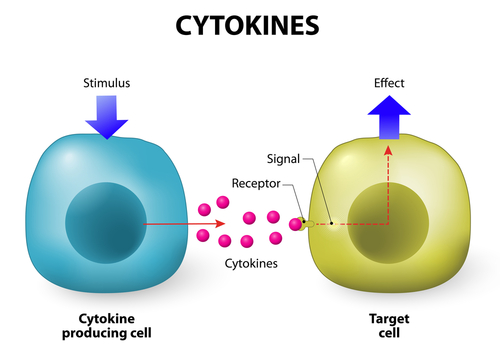

Cytokines: These are the primary chemical switches that turn the immune response on and off. They activate and recruit other cells to the immune response and assist in antibody production. Cytokines are responsible for fever production and participate in the allergic response, as well as antimicrobial and antiviral activity.5,7,8

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFɑ) is one of the most important cytokines involved in systemic inflammation; it regulates other cells of the immune response. It has antiviral and anti-tumor activity, and dysregulation is implicated in obesity, Alzheimer’s, cancers, depression, and IBD.5,7,8

Acute Phase Reactants (APR): APRs are a category of proteins produced in the liver that increase or decrease in response to inflammation. Some of the most notable are C-reactive protein (CRP), ferritin, and fibrinogen.

CRP increases rapidly with inflammation and marks damaged cells, making them easier to identify for elimination. Once it rises, it’s cleared rapidly from the system.11,12

Ferritin, an iron carrier protein, increases in response to most infections, except a few bacterial strains.11,12 Fibrinogen is a coagulation factor promoting clot formation that increases with inflammation. ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate), also considered to be an APR, describes the rate at which red blood cells fall in a one-hour period and correlates to fibrinogen levels.11,12

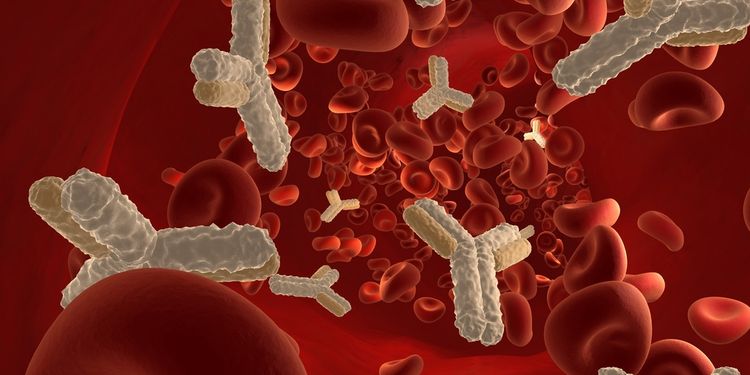

Other aspects of the inflammatory response involve the formation of antibodies to specific antigens and the blood clotting system. Antigens are proteins found on all cell surfaces, and when the immune system identifies them as foreign, it forms a corresponding antibody to it. Antibodies either neutralize the foreign invader or prepare it for phagocytosis (engulfing of a foreign particle for elimination).9

The process of blood clotting (coagulation) involves a group of proteins that convert clotting factors (such as prothrombin, thrombin, and fibrinogen) to a fibrin clot. The pathway is linked to inflammation since the clotting process, which occurs outside of a cell, can trigger the inflammatory signaling inside of a cell.

These processes operate in a feedback loop that promotes one another, and when left uncontrolled, this loop can be a problem in chronic inflammation—especially cardiovascular disease, clotting disorders, and hormone imbalances.10

All of these chemicals signal in various ways to elicit the response that produces redness, swelling, heat, immobility, and pain—as they should—but the body is smart and knows that the inflammation must end.

Dr. Robert Rountree, MD, states, “Simultaneously, the body activates biochemical counter-regulatory pathways (off switches) that produce anti-inflammatory mediators such as lipoxins, protectins, and resolvins. These are lipid mediators that are made on demand from the omega-6 fatty acid, arachidonic acid (AA), and the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) specifically for the purpose of turning off the inflammatory response.”2

This pro- and anti-inflammatory balance is the adaptive immune process, and it’s what should happen after an acute injury where the body identifies and responds to the insult or invasion, then repairs the injury and the process ends.

This process becomes a problem in two scenarios. First, when this response is exaggerated, producing a severe allergy or anaphylaxis. Second, when the cause of acute inflammation persists without end or the counter-regulatory mechanisms (anti-inflammatories) are compromised, producing chronic inflammation. Acute inflammation from a wound, infection, or a food allergy will cause systemic, chronic inflammation if not identified and treated.

Additionally, when the normal mechanisms that quench inflammation are decreased (or pro-inflammatory processes are increased), chronic inflammation will ensue. Inflammation begets inflammation, so it’s important to identify the triggers to stop perpetuating the cycle.

Functional medicine cardiologist Dr. Mark Houston says it best: “The body has a limited number of options to deal with an unlimited number of insults.”

Triggers of Inflammation

There are many triggers of inflammation, and often several are operating in concert together, propelling the cycle forward.

What these triggers have in common is that they generate free radicals or reactive species from oxidative stress and/or the inflammatory chemicals discussed previously.

Free radicals and other reactive species are produced as a product of oxidation, which involves the removal of one electron from an atom, rendering it unstable or reactive.

Your body obtains energy by combining fuel from the foods we eat with the oxygen we breathe in a controlled metabolic process that yields potentially dangerous oxidative byproducts that damage DNA, mitochondria, proteins, and cell membranes if we don’t have the appropriate antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms in place.

Oxidative stress isn’t only generated when you eat, but also during exercise, detoxification, and when the immune system is activated in the inflammatory response.

The good news is that many of these triggers are modifiable lifestyle factors or conditions that can be tested for, identified, and reversed. Dr. Mark Hyman, MD explains the importance of identifying the causes, explaining, “My job is to find those inflammatory factors unique to each person—to see how various lifestyle, environment, and infectious factors spin the immune system out of control, leading to a host of chronic illnesses.”16

The most common triggers are:

- Diet

- Stress

- Dysbiosis

- Infection

- Hormone imbalance

- Toxins

Trigger: Diet

Diet, for most people, is the single most important lifestyle change that can significantly impact chronic inflammation.

The food you eat sends chemical messages to your genes, which will either turn up or turn down inflammation. The following are pro-inflammatory foods (so you should think about avoiding them):

Gluten: A protein that has been hybridized (changed from its original form through breeding, not genetic modification) to the point that your body sees it as foreign and reacts to it. This reaction upregulates the immune system and will continue until the gluten is removed.

Food Sensitivities and Allergies: Gluten, dairy, corn, soy, yeast, eggs, and nuts are the most common offenders. When your body is constantly bombarded by these irritants, leaky gut, or increased intestinal permeability occurs, allowing larger food particles to enter your blood, and the immune system responds. Since you eat several times a day, the result can be a continuous cycle of inflammation and immune upregulation until the source is eliminated.

GMOs: Genetically modified foods that your body can’t identify can trigger an immune response similar to a food sensitivity. The largest GMO crops are corn, canola, soy, sugar beets, zucchini, yellow squash, and papaya, many of which are pro-inflammatory to begin with.

According to Dr. Tom O’Bryan, BT (botulinum toxin) in GMO foods has been shown to cause severe intestinal permeability in insects.23 Dr. O’Bryan also warns that BT toxins have been found in maternal and fetal blood, so we know they’re getting absorbed when we consume them.23

Sugar and Refined Carbohydrates: Your body is only designed to handle small amounts of natural sugar, and there are several issues with exceeding this amount.

First, refined sugar and carbs are genetically unfamiliar, which is a problem.11 Second, when you consume sugar or carbs, especially in large amounts frequently, it causes a rapid rise in blood sugar. If you need fuel, your body will use it; otherwise, it gets stored in muscles as glycogen or in fat cells.

If you have decreased insulin sensitivity or diabetes, this storage process is inefficient, leaving sugars in circulation, which spells trouble because it leads to the formation of free radicals from increased oxidation. Too much insulin release is pro-inflammatory as well.11 Excess sugar also promotes yeast overgrowth and dysbiosis (higher amounts of bad bacteria versus good bacteria), which further encourage inflammation.

Conventional Dairy and Meats: Meat and dairy raised in a conventional manner (grain-fed versus grass-fed) have the same health problems humans do, since they weren’t meant to eat grain.

Consuming all of these grains leads to a higher production of pro-inflammatory omega-6s and fewer omega-3s in these animals. When you eat them, you’re increasing your levels of pro-inflammatory fats as well. Some of the proteins (especially A1 casein) found in dairy are known to promote inflammation according to Dr. Kelly Brogan.13

Bad Fats: Most Americans have a dietary (and bodily) imbalance in their omega-6/omega-3 ratio, which causes your body to be in a pro-inflammatory state. Corn, safflower, sunflower, soy, and peanut oil are all omega-6s. Also, healthy fats such as olive oil, nuts, and nut oils are degraded (oxidized) when used in cooking at high heats or when storing them improperly, leaving them vulnerable to oxidation due to air exposure.

Consuming these now rancid (oxidized) fats is inflammatory. Chemically altered trans fats (hydrogenated oils, margarine) in processed foods are potent drivers of inflammation as well.

Processed Foods: These foods contain additives, colorings, dyes, and preservatives that your body sees as irritants or toxins. Because these foods are foreign to your body, they may induce an immune response.

Alcohol: It’s well-documented in literature that alcohol consumption decreases immune function.14 Alcohol and its by-products are direct toxins and irritants to the body, especially the gut, liver, and brain.

Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs): AGEs are produced as a result of a glycation reaction, when a sugar reacts with a protein or fat. AGEs form stable molecules that embed in tissues, causing oxidative damage, and are difficult for the body to get rid of. In food, they occur by cooking at high heat as with grilling, barbecuing, deep frying, broiling, and searing—basically anything that gives color or texture. The higher the heat, the more AGEs that form.

Meats, sugary foods, and processed foods are particularly high in AGEs. They also occur naturally in your body, and the higher your blood sugar, the more these will form, so limiting sugars and maintaining blood sugar is important. Fructose is particularly reactive, so limiting daily intake to 25 g or less is best.15

Low Phytonutrient and Antioxidant Consumption: A diet low in a broad array of plant-based nutrients is associated with increased levels of inflammation, even if you’re eating “the right things.” Decreased intake of fruits and vegetables is associated with developing inflammation that preceded metabolic syndrome and heart disease, among others.16

Trigger: Stress

Stress as a trigger for inflammation is just as important as diet is. It could be argued that stress is more so, actually, since stress comes in so many different forms that all add up when combined in our hectic modern lives.

Physical Stress: Trauma/injury, surgery, and exercise (too much or too little)

Chemical Stress: Toxins, metabolic waste and oxidation, infections, allergens, chronic illness, autoimmunity, medications, hormone imbalances, food, and drink.

Emotional Stress: Work, finances, relationships, job change, marital change, death of a loved one, birth of a child, etc. This is what people commonly refer to as “stress” in their lives. These stressors are often the hardest to control and can have a profound impact on healing.

It’s important to note that the body doesn’t discern between different types of stresses. Similarly, it can’t perceive the difference between good stress (birth of a baby or a new job) and bad stress (loss of job, divorce) and will react the same.

Anything that disrupts homeostasis will be perceived by the body as a stressor, and it will act accordingly in an effort to keep you alive.

Stress, like inflammation, is good when the response is appropriate and controlled. It initiates the ‘fight or flight’ response meant to keep you alive when danger is present (like when you encounter a bear and need to escape), like blood rushing to your brain to keep you focused. Simultaneously, non-essential functions like digestion and reproduction are decreased.

Just like with inflammation, counter-regulatory off switches exist so that the stress response ends. This was great in paleolithic times; however, in modern life, we have an overabundance of stress that doesn’t seem to stop.

Our stress response never ends, disrupting the mechanisms that should bring us back in balance. This causes several physiological changes that potentiate inflammation.

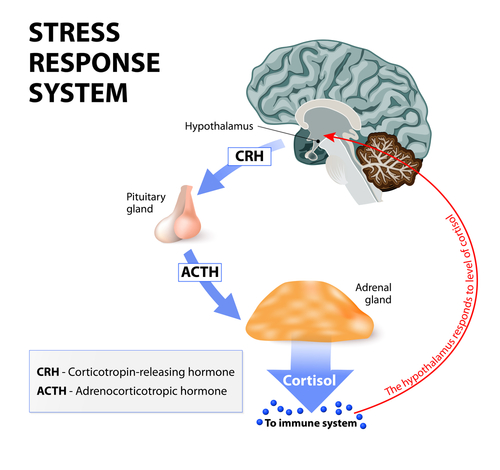

Chronic stress causes the sympathetic nervous system to be upregulated and increases levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

Over time, constant cortisol elevation leads to cortisol resistance, where the body must pump out even more to meet the same metabolic demands.

When this occurs for extended periods of time, cortisol levels become chronically low and adrenal fatigue develops. Cells of the immune system become insensitive to cortisol’s regulatory effect and don’t respond, which promotes inflammation.17

Not only does stress promote inflammation, but it also lowers immunity. A 2012 study by Dr. Sheldon Cohen revealed that prolonged exposure to a stressful event was associated with the inability of immune cells to respond to hormonal signals that normally regulate inflammation.

In turn, those with the inability to regulate the inflammatory response were more likely to develop colds when exposed to the virus. “The immune system’s ability to regulate inflammation predicts who will develop a cold, but more importantly it provides an explanation of how stress can promote disease,” Cohen said. “When under stress, cells of the immune system are unable to respond to hormonal control, and consequently, produce levels of inflammation that promote disease. Because inflammation plays a role in many diseases such as cardiovascular, asthma, and autoimmune disorders, this model suggests why stress impacts them as well.”17

Prolonged stress upregulates (turns up) pro-inflammatory genes, resulting in increased susceptibility to infection, slower wound healing and resolution of illness, and increased risk of serious illness and premature aging from the effects of cell damage.

Trigger: Dysbiosis

Dysbiosis occurs when there’s an imbalance between the beneficial and harmful organisms in you body, especially the gut.

Normally, you have helpful bacteria and even some yeast that help you digest food, produce nutrients, and protect you from harmful organisms as well as inflammation.

Dysbiosis arises when there’s a general imbalance between the good and bad flora, or when there’s a pathogen or infection present, such as SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth), Candida (yeast), or a parasite.

Research shows that a decrease in certain gram-positive bacterial species is associated with inflammation, since they’re responsible for producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), which act to decrease some of the inflammatory signaling molecules and enhance the immune response.18

Additionally, an increase of certain gram-negative bacterial species promotes inflammation because most of them contain lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in their outer cell membrane. This is an endotoxin—as the name suggests, that’s bad because it promotes inflammation by eliciting a strong immune response and contributing to leaky gut (increased intestinal permeability).

SIBO arises when there are more bacteria in the small intestines than there should be. Normally, there are much fewer bacteria in the small intestines than the colon since the small intestines function more in digestion and absorption of nutrients. SIBO infections can promote inflammation through the imbalance of bacteria, leaky gut, nutrient malabsorption, and the imbalance of histamine and serotonin.

Candida (yeast) is a fungus that aids in digestion and nutrient absorption. It’s opportunistic, becoming pathogenic and increasing in numbers if your immune system is compromised from stress or illness, or if your diet is high in sugar and carbohydrates.

Research shows that Candida infection delays healing, and the inflammation from the infection promotes further colonization of yeast, creating a vicious cycle of low-level inflammation and infection.19

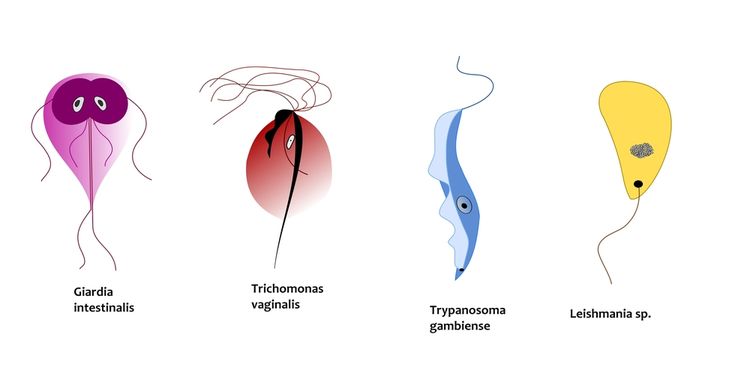

Parasites are literally everywhere. Giardia (sometimes called beaver fever) and Cryptosporidium are some of the parasites that make the headlines occasionally, even though there are a plethora that exist. Acute parasitic illness manifests with the typical symptoms of diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pain, bloating, fever, and malaise. Most resolve with the normal immune response.

Chronic infections, however, can range from asymptomatic to severe, with blood and mucus-filled stools, profuse diarrhea, and malnutrition. These infections contribute to inflammation through decreased nutrient absorption, constant immune system attack, and interrupted sleep patterns.

Trigger: Infections

Infections other than typical GI infections are also a common source of inflammation; they often go undetected for long periods of time, allowing them to wreak havoc on the body and the immune system.

Some more obvious infectious agents are mold (fungal infection), Lyme and other tick-borne illnesses, and chronic viral infections like the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Less obvious and often hidden infections that can go undetected for years are abscesses from trauma or surgery, but especially dental procedures.

Mold: Describes a group of fungi that are ubiquitous. Their spores are often airborne and deposit everywhere, which is why you find white or green fuzzy patches on your produce or bread. It can be associated with dysbiosis or systemic infection.

The toxins (mycotoxins) that come from mold are very harmful, producing symptoms ranging from mild to severe fatigue, sore throats, nosebleeds, headaches, diarrhea, brain fog, food sensitivities, and memory loss. These symptoms often mimic other conditions, which delays diagnosis and allows inflammation to proliferate.

Tick-Borne Illness: Tick-borne illnesses are becoming more prevalent and are often hard to diagnose. Lyme disease, an infection acquired through the bite of a tick infected with the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi, is the most well-known of this type of infection. Babesia, Rickettsia (Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever), Ehrlichia, and Bartonella are also frequently identified infectious bacteria from tick bites. These infections not only take a toll only the immune system itself, but also the gut, contributing to decreased GI motility and dysbiosis.

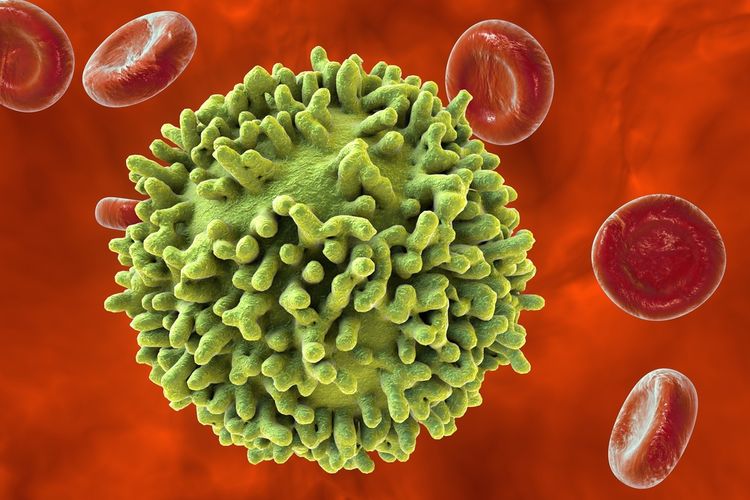

Chronic Viral Infection: A common but not often talked about cause of systemic inflammation. The problem with viruses is that they can remain latent (inactive) for extended periods of time and don’t reactivate until there’s a trigger.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) are two herpes family viruses that can remain latent after initial infection and only become active again under stress or immunosuppression. EBV, the infectious agent in mononucleosis, is also associated with the development of several types of cancer and autoimmune conditions. Chronic activation of the immune system produces inflammation with undetected viruses.

Abscesses: Can occur after any type of tissue injury such as trauma, surgery, infection, or dental procedures (especially a root canal). They form when incomplete healing takes place, either from a physical barrier or because the body can’t mount an appropriate immune response to kill off the bacteria.

The constant activation of the immune system produces chronic inflammation, and many systemic symptoms can go on for years—this is one of the most difficult causes to detect, since most people forget about a procedure or discount an injury.

Trigger: Hormone Imbalances

Hormones need to be maintained in a delicate balance for proper function. When any hormone is too high or too low, many of the other hormones shift as well, causing imbalances throughout the system.

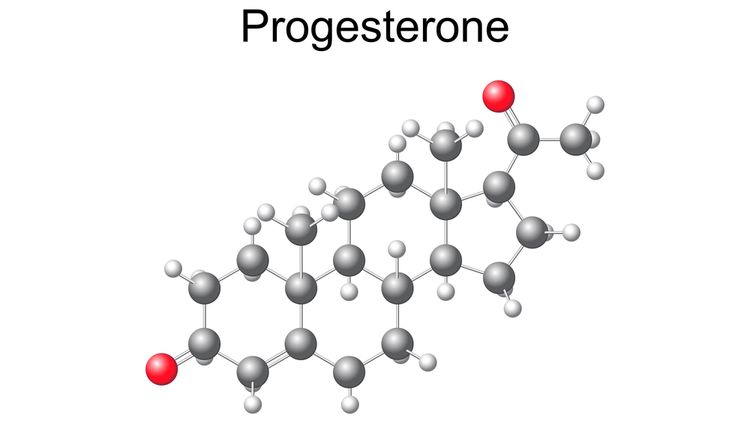

Cortisol, DHEA, insulin, estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone all have effects on each other, as well as other hormones, which all impact inflammation.

Generally, androgens (testosterone and DHEA) have a suppressive effect on the immune response and inflammation while estrogens increase the immune response. Research suggests:

“Low levels of androgens as well as lower androgen/estrogen ratios have been detected in body fluids (blood, synovial fluid, saliva) of both male and female rheumatoid arthritis patients, supporting the possibility of a pathogenic role for the decreased levels of the immune-suppressive androgens.

“Several physiological, pathological, and therapeutic conditions may change the sex hormone milieu and/or peripheral conversion, including the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, the postpartum period, menopause, chronic stress, and inflammatory cytokines, as well as use of corticosteroids, oral contraceptives, and steroid hormonal replacements, inducing altered androgen/estrogen ratios and related effects. Therefore, sex hormone balance is still a crucial factor in the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses.”

Adrenal fatigue with lowered cortisol and DHEA, estrogen dominance in women (with a relative low progesterone level), and low testosterone in men (with a relative elevation in estrogen) all create an imbalance that skews the body to a pro-inflammatory state. This state can be further exacerbated by poor blood sugar regulation.

Proper blood sugar regulation is critical in maintaining hormone and inflammatory balance. Excessive insulin is pro-inflammatory, as is the activity of the enzyme aromatase, which is increased by insulin.

Aromatase is the enzyme that converts androgens to estrogens, and it has a great deal of influence on the production and balance of sex hormones. Many cell types have aromatase activity, but adipocytes (fat cells) are of particular interest because the more you have, the more active aromatase is.

If you’re insulin-resistant, diabetic, or overweight, the enzyme aromatase will become upregulated, promoting inflammation. Insulin resistance (high insulin levels) and excess body fat increase estrogens, which increase aromatase and inflammation in a vicious cycle.

In addition, elevated blood sugar levels from insulin resistance create more inflammatory compounds, worsening the situation. This is why poor blood sugar regulation combined with excess body fat creates the perfect inflammatory storm and provides a base for many chronic illnesses.

Trigger: Toxins

Toxins are virtually all around us in modern life, from pollutants in the air we breathe, the water we drink and bathe in, and the foods we consume to the products we use to clean ourselves, our homes, and our possessions. They can also be produced in the cooking process and in our guts.

The process by which toxins cause inflammation is multifactorial. According to Chris Kresser, LAc, MS, “Environmental toxins interfere with glucose and cholesterol metabolism and induce insulin resistance; disrupt mitochondrial function; cause oxidative stress; promote inflammation; alter thyroid metabolism; and impair appetite regulation.”

The thyroid is particularly sensitive to chemicals and oxidative stress. With increased exposure, thyroid function decreases, producing a hypothyroid state that triggers weight gain and supports inflammation.

Toxins you’ll want to minimize exposure to include heavy metals (mercury, lead, aluminum, arsenic, cadmium, etc), tobacco smoke, air pollution outside and in the home, pesticides (organophosphates), herbicides, plastics (BPA, BPF, BPS, phthalates, polystyrene, PVC, etc.), chemicals (toluene, xylene), and preservative and chemical-laden personal care products and foods. This list is a good place to start, but it’s not exhaustive.

Toxins can also come from cooking at high heat. When food darkens in color, it not only produces AGEs but also heterocyclic amines (HCAs), especially in meats. Consumption of HCAs is linked to many types of cancer since it alters genes (mutation) and promotes inflammation.21 And if your detoxification systems are impaired, the effects can be magnified because of the free radicals and oxidative stress generated. Dr. Robert Rountree says, “Eating a burnt burger is really no different than smoking a cigarette.”24

Symptoms of Inflammation

Anything that ends in ‘itis’ means that it’s inflamed. Appendicitis literally translates to “inflammation of the appendix.” Other than the obvious ‘itis’ conditions, here are other symptoms associated with chronic inflammation:

Immune: Allergies, asthma, autoimmune disorders, chronic or recurrent infections that won’t resolve (such as sinusitis or UTIs)

Skin: Dermatitis, eczema, acne, rashes, hives, redness, pruritis (itchiness), petechiae (broken blood vessels)

Gastrointestinal: Food sensitivities, food allergies, GERD (acid reflux), IBS, IBD, and infection or dysbiosis that can produce gas, bloating, diarrhea, or constipation

Brain and Mood: Headaches, brain fog, poor memory, depression, anxiety, irritability, fatigue, lethargy, dementia

Nerves: Tingling, pins and needles, paresthesia

Hormonal: Poor blood sugar regulation (especially high blood sugar), weight gain or loss, imbalanced female and male hormone systems, poor sleep quality, thyroid imbalances, adrenal imbalances

Cardiovascular: Hypertension (high blood pressure), high cholesterol, anemia

Musculoskeletal: Joint and muscle pain, fibromyalgia

Liver: Poor detoxification, elevated liver enzymes

Chronic inflammation affects literally every cell in your body. Virtually all significant diseases and conditions are related to chronic inflammation.

If the above symptoms are ignored, they can become a full-blown condition like a heart attack, congestive heart failure, diabetes, cancer, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s, Celiac, Hashimoto’s (autoimmune hypothyroid), Grave’s (autoimmune hyperthyroid), stroke, Lupus, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, psoriasis, scleroderma, hepatitis, pancreatitis, autism, ADD/ADHD…the list goes on.

Lab Testing for Inflammation

Testing for inflammation can be exhaustive. This is a good list to start with to investigate general inflammation.

Root cause testing, including allergens, food sensitivities/allergies, heavy metal and toxin exposure, mycotoxicity, GI infections and dysbiosis, hidden infections, autoimmune conditions, and hormone testing may also be necessary.

General Inflammation:

- High sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Ferritin

- Homocysteine

- Lipoprotein a (Lp(a))

- Apolipoprotein A1 and B (Apo A1 and B)

- Complete blood count

- Vertical Auto Profile (VAP) cholesterol test or lipoparticle protein testing (LPP)

Adrenal Testing:

- Salivary cortisol testing with DHEA

Blood Sugar Regulation:

- Blood glucose (blood sugar)

- Fasting insulin

- Hemoglobin A1C

Oxidative Stress:

- Telomere testing

- 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG)

- Lipid peroxides

Treatment of Inflammation

The treatment of inflammation can seem daunting since there are so many different causes.

The easiest approach is to clean up the diet, add in nutrients and make lifestyle modifications.

If you’re not getting the desired results, do some further investigating into root causes such as food allergies, autoimmunity, GI infections, impaired detoxification, toxic exposures (mycotoxins, heavy metals, chemicals), hidden infections such as Lyme or EBV, and proper hormone balance.

Diet: Dr. Mark Hyman, MD suggests, “Eat an organic, whole foods, high fiber, plant-based diet, which is inherently anti-inflammatory. That means unprocessed, unrefined, real food high in powerful anti-inflammatory plant chemicals called phytonutrients.”27

As Dr. Josh Axe notes, “Antioxidants are self-sacrificing soldiers that donate an electron to neutralize free radicals and are consumed in the process.” He suggests eating brightly-colored vegetables and fruits, cocoa, and green or white tea.25

Dr. Hyman also recommends getting an oil change. “Eat healthy fats from olive oil, nuts, avocados, and omega-3 fats from small fish like sardines, herring, sable, and wild salmon.”27 These fats are anti-inflammatory and promote a healthy omega 3:6 ratio.

An elimination diet may help you find out if there are foods contributing to your inflammation. Eliminate these foods for at least 30 days and note how they make you feel when you add them back in.

Cooking your foods at a lower heat will help them retain nutrients and avoid forming harmful substances. Author Mark Sisson recommends poaching, boiling, steaming, braising, baking, or using a pressure cooker or crock pot.28 If you really want to grill or cook at high heat, marinating with olive oil, citrus, and herbs or spices will reduce toxin formation.

Nutrients and Supplements: There are many anti-inflammatory nutrients found in fruits, vegetables, teas, coffee, herbs, and spices. Here are some that can be helpful if you experience inflammation:

Magnesium and vitamin D exert anti-inflammatory action by decreasing cytokine production and prostaglandins, respectively.1,31

Vitamins C and E, zinc, and selenium function as antioxidants and protect against oxidative stress.

Curcumin blocks activation of a key protein that triggers the immune response and decreases cytokine activity according to research out of Ohio State University.29

Ginger is a root that has uses in many ancient traditional medicine systems. Ginger is an anti-inflammatory and a blood thinner.30

Boswellia (frankincense) is an Ayurvedic herb that, when taken orally or topically, provides anti-inflammatory properties through inhibiting pro-inflammatory enzymes.30

Alpha lipoic acid (ALA) functions as an antioxidant and supports healthy mitochondrial function.31

Essential fatty acids (EPA and DHA) from fish oil or krill oil is important since humans don’t efficiently synthesize it themselves. They modulate the inflammatory response and maintain balanced fatty acid ratios.1

Probiotics (“good bacteria”) increase the levels of healthy bacteria in your gut, which reduces inflammation.

According to neurologist Dr. David Perlmutter, turmeric (curcumin), green tea extract, pterostilbene (from resveratrol), glucoraphanin (from broccoli), and coffee activate an important anti-inflammatory pathway (Nrf2), and taking these nutrients as supplements can be far more effective at increasing antioxidant production than typical antioxidants.26

Lifestyle Modifications: These are some of these easiest and most effective ways to reduce inflammation. Incorporating them into your life as habits will help promote long-term inflammation management.

Exercise: This is one of the most effective ways to decrease inflammation, since it has so many benefits—improved insulin sensitivity and body composition, decreased stress (when you don’t overdo it), and decreased signaling of inflammatory chemicals.32

Stress reduction: Stress is one of the biggest contributors to chronic inflammation, and managing it essential to lifelong health. Identifying stressors is the first step. Once you’ve done this, create boundaries, say “no” when you have to, and make sure your feelings are heard and understood.

Relaxation: Learn to actively relax to engage your vagus nerve, the powerful nerve that relaxes your whole body and lowers inflammation, by doing yoga, meditation, deep breathing, or even taking a hot bath.27

Sleep: Getting adequate sleep is essential to healing. Aim for a minimum of 8 to 9 hours per night, and try to get to bed by 10 PM. Sleep in a dark, cool, and quiet room for the most restful results.

Unplug: Being constantly tuned in to your phone, computer, iPad, tablet, or TV exposes you to radiation and can also alter your sleep cycle due to blue light stimulation.

Detox your personal care products: If you won’t eat it, don’t put it on your body. Opt for natural or organic lotions and creams, shampoo, conditioner, toothpaste, deodorant, and fragrance. You can make many for low cost at home from coconut oil, essential oils, and other common household items.

Detox your home: Look for natural and organic products here too to avoid toxic chemicals. Many cleaners are now being made from enzymes and plant soaps. You can also make homemade ones from vinegar, lemon juice, baking soda, essential oils, and more. Keeping lots of green plants in the home helps detox the indoor air as well. Look for rubber plants, aloe, peace lilies, areca palm, golden pothos, and English ivy.

With a little detective work and some requisite effort, you could be well on your way to putting out the fire from within your own body that’s robbing you of your health. Learn to listen to your body and to notice the obvious signs. Your body is an incredible machine that’s designed to want to heal. All it asks of you is to provide it with an environment that’s conducive to this objective.